Kentish Flats Wind Farm - 6th February 2010

5 miles North of Herne Bay lie 30 wind turbines 115 metres tall arranged in a square of North Sea 1.5 miles across. We went there on 6th February 2010. http://www.kentishflats.co.uk

Then we went two miles further to the 6 deserted WW2 forts of Shivering Sands.

Good photo here Shipping Channel

You can see photos of the trip here

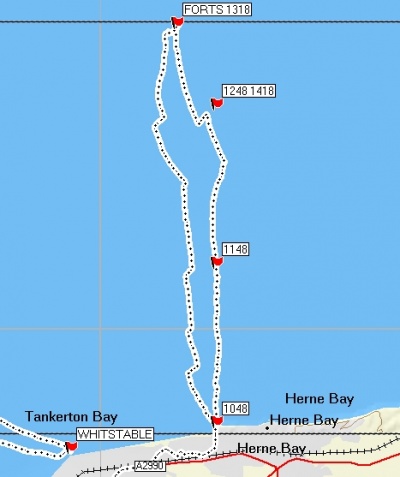

Here is the route we took. The right hand track is the route out and the left hand track is the route back. The '1248 1418' flag marks the northern edge of the wind farm, the southern edge is where we change course to head South on the way home.

You can see how far we drifted West in our short breaks and also how steering 130 degrees (more like E than S) was needed to get us to go more or less South. Our straightest steady course is the section to the forts. Amazing what the sight of a supertanker bearing down on you will do.

This was a really nice trip. After a bit of haze lifted early on we had over five hours of sunshine, with brochure style views of dramatic wind turbines, huge ships at close quarters and WW2 forts. The experience changed a bit when the fog rolled in for the last hour though, so I thought I’d write up lessons to learn instead of a blow by blow account. So here is a list of things we knew already. Some of which we remembered, some of which we will next time. (In roughly chronological order through the trip for those of you who think a trip report should actually tell you what happened on the trip.)

It’s quite hard to paddle a straight course to a target 2 miles wide. Which one of the thirty identical turbines are we aiming at again?

Trust the compass over your eyes. It was very easy to head towards the structure we could see even though it didn’t look like the forts and wasn’t in the right place.

On a sunny day visibility can still be restricted. On the day we could see 2.5NM. At that distance container ships are really huge when you first see them.

Container ships go really fast. It took them about 7 minutes to get to us from the moment we first saw them.

Container ships that are pointing right at you are harder to see. Maybe 4 minutes away.

Container ships can turn really quickly. That’s not what I’d been told. So many lectures about how ships can’t see you and can’t move out of the shipping lane and take 10 miles to come to a stop. No one told me that if the shipping lane turns right by 90 degrees, so do they, in about 10 seconds, without slowing down at all. Which means all that stuff about knowing you aren’t on a collision course if the bearing is changing doesn’t help too much. We weren’t on a collision course but now she’s turned like a homing missile and is coming right at us. (Actually for us it worked the other way. A ship that was racing us to the shallow water turned across our course and then aimed behind us. All without seeing us, and all from very close.)

Distance to the horizon in a kayak is 2NM. So if you are 4NM away from low-lying land you won’t see it for 40 minutes.

Not getting out of the boat for seven hours has several effects. There’s an obvious need to use a bathroom (‘no, Mr. Coastguard, I’m not just feeling like that because of the cold.’) But it also means it’s harder to eat lunch, or drink enough, and that your core balance muscles never get a break, all of which makes you more tired than normal towards the end of the trip. You also never get to ‘re-set’ how you feel about the trip, so any scares (super-tanker surfing anyone?) continue to effect your paddling to the end of the trip. Even on a trip along the coast it would be good to plan to stop and ‘re-set’ after any more challenging conditions.

Being able to see where you are heading is very important. When we could see home it was really encouraging… until the fog came in and took the land away again. That was really depressing.

Dressing warmly isn’t just about being dressed for immersion. Even if you don’t fall in it’s good to be dressed warmly enough for the management of any incidents. We spent an hour either towing at reduced speeds or stopped to set up the tow. Cold February winds plus slow speeds had serious impacts even through a dry suit and thermals. Ideally your clothes need to be warm enough to keep you capable of accessing and using your rescue equipment or of being the support paddler in a tow for up to an hour.

The coastguard are really good people and will contact you if they see fog coming, just to see if you’re OK. That’s really encouraging. It’s well worth keeping the VHF on and monitoring channel 16.

When the coastguard contacts you, it’s OK to pause before replying. That way you don’t do stupid things like give your position as two miles inland, or drop an open drybag full of kit into to the sea.

It doesn’t matter how close you are to land, at the moment a tow or other incident begins you need to plan to be cold for a significant period of time. While some paddlers are arranging the tow, the others need to be getting out shelters and spare clothing for the casualty and others involved in the rescue. We were 1.1 miles out but it took almost an hour to get to the beach.

Safety kit needs to be accessible as well as present. Kit in the large hatches isn’t accessible at sea; it needs to be in the day hatch or in the cockpit or on your person. But kit is also not accessible if you’ve stuffed so much into the day hatch that it requires superhuman strength to get it out (thanks Terry for providing the muscle.)

Trust the compass. Wind doesn’t only blow the boat sideways, it also makes you want to paddle downwind. Each stroke is just slightly easier if it’s just slightly off course and in fog your brain tells you that’s keeping exactly straight.

A compass attached to your boat is much easier to follow a course on than a handheld. Especially when you are approaching your limits for things like letting go of the paddle to unzip your pfd.

GPS is great. That’s true despite all the books telling you never to rely on it and that you’re betraying the spirit of the Esquimaux if you carry one. The difference between a bearing that you have worked out to bring you in to shore and a bearing that you KNOW is bringing you in to shore is massive. Your eyes and sense of direction (and therefore the eyes of everyone else in the group) will say the bearing is wrong. It helps you sound confident if you know exactly where the group is.

If the distance to travel should take 5.5 hours then it’s good to leave spare time for breaks and safety time for return before nightfall. I planned an hour and a quarter spare. In addition we left forty minutes early (which has never happened before on any Tower Hamlets trip since I joined the club eleven years ago.) We needed every minute which means an hour and a quarter was not enough.

When your brain says at launch ‘there’s a steep bit of beach. I’m glad it’s low tide so we can use the flat bit further out’ – it’s probably a good idea to work out where the tide will be when you come back. Especially if another bit of your brain knows the wind might be creating waves onto the beach by then.

If landing through surf, take your paddle leash off first otherwise it will wrap round your legs on landing and cause you to fall at the feet of the coastguard you were hoping to persuade to trust your judgement.

The coastguard are really good people and it’s nice to see them on the beach (even if their vans do look like the RAC.) Their vans are really warm but they like their blankets back.

It’s nice to be back in the Prospect at the end of a tiring day.

Looking forward to next time with the same people.